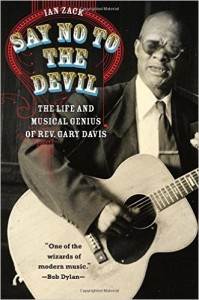

Gary Davis Bio – Say No To The Devil – Book review

Imagine for a moment living in New York City, say, sometime in the late ’40’s or early ’50’s, and while out for a walk coming upon a blind street preacher in Harlem, playing divine Piedmont style blues guitar riffs while offering a soul-stirring sermon revolving around that hypnotic music and The Holy Spirit — something close to “Holy Blues.” That is the world Ian Zack explores in his clear-eyed biography of Reverend Gary Davis, Say No To The Devil. Here, Zack follows the blind guitarist and street preacher through his hardscrabble, poverty-riddled childhood in South Carolina, his struggles against racism as an adult black man trying to survive as a street performer and itinerant preacher in the Jim Crow South, and eventually to his life in New York City as teacher, mentor, and inspiration to many young folk musicians and popular artists growing up in the Northeast during the late 1950s and ’60’s. Zack throughly researches Davis’s life, and in prose as clean as baptismal water he breathes life into the history of one of the most important — and perhaps least known —influences on modern American music.

Imagine for a moment living in New York City, say, sometime in the late ’40’s or early ’50’s, and while out for a walk coming upon a blind street preacher in Harlem, playing divine Piedmont style blues guitar riffs while offering a soul-stirring sermon revolving around that hypnotic music and The Holy Spirit — something close to “Holy Blues.” That is the world Ian Zack explores in his clear-eyed biography of Reverend Gary Davis, Say No To The Devil. Here, Zack follows the blind guitarist and street preacher through his hardscrabble, poverty-riddled childhood in South Carolina, his struggles against racism as an adult black man trying to survive as a street performer and itinerant preacher in the Jim Crow South, and eventually to his life in New York City as teacher, mentor, and inspiration to many young folk musicians and popular artists growing up in the Northeast during the late 1950s and ’60’s. Zack throughly researches Davis’s life, and in prose as clean as baptismal water he breathes life into the history of one of the most important — and perhaps least known —influences on modern American music.

In fact, it would be quite difficult to overestimate Davis’ influence upon Twentieth Century music. One can directly trace the development of musicians and bands such as Bob Dylan, Peter, Paul, and Mary, The Grateful Dead, Ry Cooder, Keith Richards, and The Jefferson Airplane, directly to Davis’s mentoring and teaching — and this is just the short list. As Grateful Dead guitarist Bob Weir, one of Davis’s many students, remembers, “[Davis] had a Bachian sense of music, which transcended any common notion of a bluesman.” While reading though this biography one begins to realize that modern popular music, not just the blues, owes a substantial debt to Gary Davis.

By all accounts — and there are many in this book — Davis possessed a preternatural ability on the guitar, and in keeping with the mythic nature of his abilities, Davis’s first guitars were home-made affairs he assembled from his grandmother’s pie pans, using small pieces of lumber for the neck and copper wires for strings. Zack explains that “for [Davis’s] efforts, his grandmother usually whipped him.” Perhaps pie plates were in short supply in South Carolina.

Zack fills this biography with many examples of Davis’s ability to survive as a street performer and preacher. For example, to attract and hold his audience in place, Davis would use “his bag of street performer’s tricks — making his guitar mimic the human voice, as when he slid his fingers up and down the strings to simulate shouting ‘good God.’” Or, later when Davis would “[play] notes or entire chords with his left hand while keeping time with his right by snapping his fingers or beating on the guitar top or strings with his palm.” Davis would also echo the sound of an entire band by “using moving bass lines, counterpoint, rhythms variations, and changes in timbre.” All this, Davis later noted in an interview, was “to bring some brightness to the minds of the people about how we should do, how we should live.”

Not that Davis always took his own advice. Despite his saintly music, Davis was far from a saint. He enjoyed his whisky and his ladies in equal measure, and Zack portrays Davis as a man with a sackful of faults. Of course, any good biographer will attempt to humanize his subject, and in Davis’s case, Zack successfully give us a portrait of a man pursued by demons who in the end manages to fend them off — most of the time.

Davis was a master (some argue THE master) of the Piedmont blues, a style that echoes the ragtime musical structure popular in the late nineteenth century, and Zack examines in detail the influence that Davis’s style of fingerpicking had on the burgeoning folk music scene in New York City. He also describes several of Davis’s performances at various folk and jazz festivals. It was through his connections to this folk music and his performances in these festivals that Davis was “rediscovered” and became a mentor to young musicians such as Joan Baez and a seventeen-year-old Bob Dylan. But, as accomplished as musician Davis was, he rarely played the blues in public until quite late in life, preferring instead to use his vast musical talent to extend the kingdom of God.

Ian Zack has produced a well-written, enjoyable, and informative biography of Rev. Gary Davis — a musician whose gifts we still appreciate and whose influence we still feel. Hallelujah, Brother.

Say No To The Devil: The Life and Musical Genius of Rev. Gary Davis.

Ian Zack, Author; The University of Chicago Press, 323 pages. $30.00